Made in China 2.0: A transformation into the world’s strongest industrial base—empowered by artificial intelligence, driven by green energy, and oriented toward self-sufficiency.

Image source: Reuters

Guo Yiguang

World Economic Forum Contributor

Host of the "China Talk" (Sinica Podcast) podcast channel

"Made in China 2025," announced in 2015, set the tone and pace for China's industrial ambitions.

Today, this strategy is entering a new phase: a transformation into the world's most robust industrial base—empowered by artificial intelligence, fueled by green energy, and driven by a focus on self-sufficiency.

The real question now is no longer whether China can innovate—but rather what kind of innovation ecosystem it’s building, and how it’s redefining global manufacturing.

Launched a decade ago, "Made in China 2025" is seen by many as a symbol of China's ambitious industrial plan—a nationally driven roadmap aimed at propelling the country from being the world’s factory to the pinnacle of advanced manufacturing.

Its objectives have continuously evolved, adopting labels like "dual circulation" and "high-quality development," ultimately becoming the cornerstone of China's industrial strategy.

Today, this strategy appears to be entering a new phase—we might call it "Made in China 2.0." While it doesn’t yet have an official name, its contours are becoming increasingly clear: a transformation into the world’s most robust industrial base, powered by AI enhancements, fueled by green energy, and driven by self-sufficiency. From electric vehicles and solar panels to humanoid robots and enterprise-grade AI systems, China is already setting the pace for how competition will unfold on the global stage.

This transformation is unfolding amid profound global changes. Supply chain fragmentation, the rise of technological nationalism, and growing concerns about overcapacity have collectively created a fiercely competitive landscape in global manufacturing. Yet, even amidst this turbulence, China continues to strengthen its industrial and technological influence. Today, the real question is no longer whether China can innovate—but rather what kind of innovation ecosystem it is building—and whether this could potentially emerge as an alternative paradigm to the free-market model.

Made in China 2025: Progress and Pitfalls

"Made in China 2025," first unveiled in 2015, was designed to outline a blueprint for industrial transformation. Its goals are ambitious: reducing reliance on foreign technology and elevating China’s position in the global value chain across 10 strategic sectors—ranging from semiconductors and advanced robotics to aerospace and biopharmaceuticals. Inspired by Germany’s "Industry 4.0" initiative, "Made in China 2025" aims to establish China as a global leader in high-end manufacturing by the time the People’s Republic of China celebrates its centennial in 2049.

Although "Made in China 2025" is hailed as a comprehensive industrial master plan, it has never actually been a detailed policy blueprint. Instead, it serves more as a directional roadmap, outlining broad strategic goals and priority areas while also setting key performance indicators for local governments, Party and government officials, and state-owned enterprises.

These key performance indicators—such as achieving a certain level of domestic market share in strategic technology sectors—have become the rallying points for mobilization. However, "Made in China 2025" provides only limited implementation guidance, leaving ample room for interpretation at the provincial and municipal levels. This ambiguity, in turn, raises the potential for policy duplication and misalignment. In this sense, "Made in China 2025" functions as a signaling device: it underscores China’s ambitious vision for industrial development while setting the pace for resource allocation, political priorities, and institutional experimentation.

In some respects, "Made in China 2025" has already yielded significant results. Today, China holds a dominant position in key green technology sectors: it accounts for more than 75% of global lithium-ion battery production, nearly 80% of solar panel manufacturing, and an overwhelming share of the world’s electric vehicle output. Meanwhile, high-speed rail has become a flagship showcase of China’s engineering prowess. And in the rapidly advancing fields of robotics and sensor technology, China’s impressive growth is steadily narrowing the gap with the world’s leading nations.

However, the plan has also fallen short of expectations in several key areas. China still relies on foreign technology for advanced semiconductors and critical high-end components. Additionally, domestic R&D efforts in biopharmaceuticals and next-generation aircraft have lagged behind initial projections.

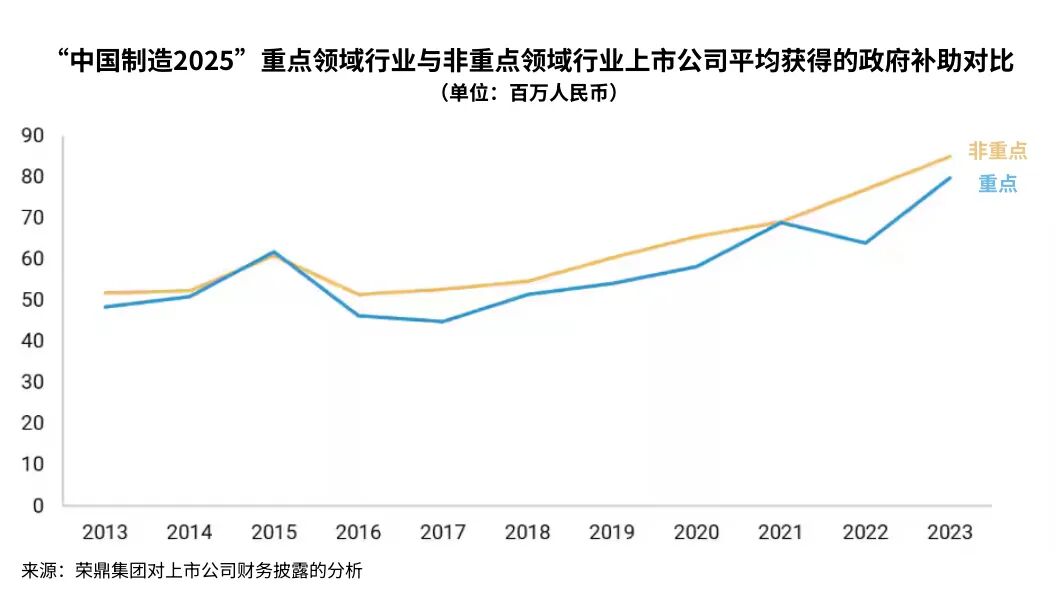

According to recent assessments, including a report by Rhodium Group, some of the shortcomings of "Made in China 2025" stem from certain systemic design flaws: redundant investments across regions, misaligned local incentive mechanisms, excessive reliance on subsidies, and an overemphasis on the production side of the economy at the expense of household needs.

Moreover, the high-profile launch of this initiative has also drawn unwarranted geopolitical attention. It has sparked concerns in the U.S. and Belgium about state-led technological mercantilism, prompting the introduction of export controls and investment restrictions. Although the slogan "Made in China" has faded from official discourse, the strategic ambitions behind it remain intact—albeit being pursued now in a more subtle, yet equally assertive, manner.

"Made in China 2025" may better be understood as a catalytic phase—it serves as an initial framework that helps mobilize investment, drive industrial upgrading, and instill a long-term vision. By establishing a robust industrial blueprint, it enables China to continuously refine and expand upon this foundation, laying the groundwork for transitioning into a more decentralized, networked, and innovation-driven stage of development.

The Compound Engine Behind China's Industrial Growth Momentum

One of the most striking features of China's industrial rise is the mutual reinforcement among its key sectors. As Princeton University researcher Kyle Chan puts it, China's innovation system isn't made up of isolated, vertically structured industries—it’s instead a complex, interconnected ecosystem where sectors overlap, intertwine, and continuously nurture one another. Advances in one area—such as lithium batteries, for instance—spill over into other fields like electric vehicles, consumer electronics, and energy storage systems, creating ripple effects. In turn, demand from these downstream sectors drives upstream industries to scale up production and spur even more innovation.

Take the smartphone supply chain as an example. Its evolution has not only led to cheaper, more efficient components but has also spurred specialized advancements in compact displays, lightweight materials, and precision manufacturing—features that are now benefiting the electric vehicle industry. Similarly, breakthroughs in battery chemistry originally developed for electric scooters or drones are now driving innovations in grid-scale energy storage and smart energy applications. Meanwhile, artificial intelligence and robotics are amplifying these synergies, enabling a comprehensive leap forward in automation and optimization levels.

This systemic interdependence has become the powerful, multi-faceted engine driving China's industrial growth. As a result, not only is scaling happening faster, but it’s also accelerating the learning curve, reducing costs, and enhancing iterative capabilities. This empowers Chinese companies with strategic autonomy—and the ability to swiftly adapt when circumstances shift, a critical asset in today’s fragmented and rapidly evolving global economy.

"Process knowledge" and practical experience

Behind this ecosystem advantage lies something more fundamental: the accumulation and deepening of "process knowledge." While Western economies—particularly the U.S.—have grappled with the hollowing out of their manufacturing sectors, China has taken the opposite approach. Instead of shrinking its domestic production networks, it has steadily expanded and upgraded them along the value chain, embedding knowledge deeply into the everyday processes, tools, and people that form the bedrock of real-world innovation.

"Process knowledge" refers to the tacit, experiential knowledge accumulated in factory workshops, supply chain coordination, and the trial-and-error process of prototyping. As everyone knows, this type of knowledge is notoriously difficult to codify—but it remains absolutely critical for turning designs into production and transforming inventions into large-scale applications. Without it, even the most cutting-edge laboratories would struggle to achieve scalability.

Analyst and Stanford University researcher Dan Wang offered a memorable analogy in the 2023 New Star documentary I helped produce, titled "Inside China's Tech Boom"—he compared it to cooking. He said, "You can have the best kitchen, the finest ingredients, and the most perfect recipe, but if you’ve never actually cooked before, you might even struggle to fry an egg properly. Having the tools and the blueprint isn’t enough—you need hands-on experience through practice."

In China, this kind of experience is everywhere. Engineers frequently move between design and production roles. Suppliers and manufacturers collaborate closely in day-to-day operations, fostering real-time communication. As a result, iteration cycles have shrunk dramatically—from taking years to just weeks or even days. This seamless integration of R&D and manufacturing has created a powerful flywheel effect: production fuels innovation, while innovation, in turn, drives continuous improvements in manufacturing. Yet, in organizations that still view R&D and production as separate, self-contained entities, this highly effective model is often overlooked.

As we look ahead to the potential "Made in China 2035," this structural advantage—blending innovation with manufacturing—could prove to be China's most enduring, yet often unseen, asset.

Only those who learn fastest will survive.

China's industrial advancement is not merely the result of national planning or infrastructure development. Instead, it’s being reshaped by the vision, capabilities, and ambitious aspirations of a new generation of entrepreneurs—people who are redefining what "Made in China" truly means and injecting fresh vitality into the country’s industrial growth. Far from being confined to traditional manufacturing, these emerging entrepreneurs are now focusing on integrated systems thinking, cutting-edge technology, and building robust global competitiveness for their businesses.

As recently discussed at the World Economic Forum’s 2025 Annual Meeting of the New Champions, these entrepreneurs are navigating a high-risk environment marked by weak global demand, supply-chain diversification, and ongoing trade tensions. Yet, many of them are displaying an increasingly strong sense of confidence—partly because they initially entered the startup scene under intense pressure: fierce domestic market competition, zero tolerance for inefficiency, and a rapidly evolving landscape. In this dynamic, it’s not just about survival of the fittest—it’s about who can learn and adapt the fastest.

In fields like electric vehicles, solar energy, robotics, and artificial intelligence, China's most successful companies are often those that have mastered the art of thriving with minimal government support—thriving by rapidly iterating and aggressively expanding. For instance, BYD, thanks to its vertically integrated model, has not only kept costs in check but also accelerated its innovation cycle, enabling it to outpace competitors in both price and performance. Meanwhile, EV companies like XPeng and NIO are redefining premium automotive offerings within the Chinese context—often starting from day one with a clear global vision embedded in their strategies.

Meanwhile, China’s cultural value in industrial achievements has been reaffirmed. As the country shifts from a platform-based economy and speculative tech ventures toward real-economy innovation, these entrepreneurs are being reimagined as central figures in the nation’s narrative—they’re not only generating wealth but also contributing to technological sovereignty and climate goals. While public-private partnerships don’t always run smoothly, they increasingly highlight complementary strengths: combining the long-term national vision with the short-term agility and adaptability of entrepreneurial leaders.

This transformation is particularly evident in "cutting-edge" fields such as AI+, robotics, and smart manufacturing. In these areas, entrepreneurs are not only adapting to existing markets but also helping to create entirely new ones. Their confidence stems not just from China's sheer scale, but more importantly, from their own willingness to take bold risks, embrace rapid trial-and-error processes, and act as pioneers.

Artificial intelligence as infrastructure and intelligent manufacturing

Global discussions about artificial intelligence still revolve around AI as consumer-facing products: chatbots, co-pilots, and image generators. But in China, a more structural perspective is gradually gaining dominance: AI is no longer viewed as a standalone technology, but rather as infrastructure— the invisible foundation underpinning the next phase of industrial transformation.

This perspective is clearly evident in the consolidation of China's manufacturing sector. In smart factories, AI can optimize energy consumption, predict maintenance needs, and enable real-time, fine-tuned production adjustments. In logistics, it seamlessly coordinates fleets and warehouses with near-perfect precision. And in fields like electric vehicles and robotics, AI has become less a standalone feature and more of a foundational operating system.

The term "AI+" has already entered official vocabulary, highlighting AI's role as an enabling technology. As discussed by attendees at the "AI+ Era" breakout session during the World Economic Forum’s 2025 Annual Meeting of the New Champions, this concept positions AI as a general-purpose technology whose true value lies in its ability to empower industries across the board. It’s not just about winning the chatbot race—it’s about redefining productivity, quality, and the capacity for scalable customization.

Equally important is the emerging open-source orientation within certain sectors of China's AI community. Models like DeepSeek are gaining traction not only for their outstanding performance but also because they’re easily accessible, sparking both government enthusiasm and market confidence. This growing accessibility is now spreading to second- and third-tier cities, small and medium-sized enterprises, and traditional manufacturers—much like how smartphones once catalyzed the development of a broader hardware ecosystem. In doing so, it’s democratizing innovation in a way that’s difficult for centralized AI strategies in other countries to replicate.

Crucially, the deep integration of artificial intelligence with manufacturing has strengthened the feedback loop between software and hardware—creating a synergy that puts China in a uniquely advantageous position. When design, engineering, and production are all concentrated within a tightly knit industrial cluster, new tools can be tested and refined on-site in just days, rather than months. This "short-cycle innovation" is fast becoming a defining feature of China’s smart industry. If China succeeds in embedding AI into an industrial operating system, it will likely reshape the global understanding of what “smart manufacturing” truly means.

The boundary between "technology" and "industry" is blurring.

What exactly does "Made in China 2035" mean? Clearly, if this trajectory continues—building on the lessons learned from "Made in China 2025," while leveraging advancements like artificial intelligence, electrification, and self-reliance to accelerate growth—then "Made in China 2035" could very well lead the world, rather than merely catching up with other nations.

We can foresee that industrial leadership will be redefined—moving beyond mere reliance on scale and instead placing greater emphasis on speed, sustainability, and system integration. Chinese manufacturing is likely to become more vertically integrated, while also embracing modularity, enhanced interoperability, and digitally driven collaboration. Meanwhile, already highly concentrated and synergistically powerful industry clusters may evolve into "computational zones," seamlessly merging physical production with digital collaboration.

Although supply chains have already been de-risked and diversified due to geopolitical reasons, they will continue to rely on the unique advantages of China's core manufacturing regions. Regions such as the Yangtze River Delta and the Greater Bay Area in the Pearl River Delta will serve as innovation hubs, driving the collaborative development of next-generation materials, advanced energy systems, and cutting-edge human-machine interfaces.

In such a future, the boundary between "technology" and "industry" will completely vanish. Artificial intelligence won’t just support manufacturing—it will become an integral part of its very DNA. Robotics won’t merely automate tasks; they’ll also redefine how products are conceived, iterated, and delivered. Meanwhile, materials science is merging with biotechnology and environmental engineering to give rise to groundbreaking innovations like self-healing composites, energy-generating fabrics, or waste-neutral production cycles.

The "export" of standards and models is equally important. Just like high-speed rail and green energy technologies, China’s manufacturing model—characterized by efficiency, speed, and seamless integration with artificial intelligence—could become a blueprint for countries in the Global South, as well as for select developed nations. "Made in China" will no longer simply signify cost-effectiveness; instead, it will stand for exceptional design, minimalist carbon emissions, and software-driven manufacturing.

Of course, none of this is set in stone. But the framework is already taking shape, and the momentum is strong. If "Made in China 2025" was a bet on capability, then "Made in China 2035" will be a bold wager on systemic synergy and consistency—specifically, how to build a system that can learn, adapt, and continuously improve itself. According to this vision, manufacturing is no longer the ultimate goal; instead, it will serve as the engine driving the collaborative growth of other sectors as well.

The above content solely represents the author's personal views.This article is translated from the World Economic Forum's Agenda blog; the Chinese version is for reference purposes only.Feel free to share this in your WeChat Moments; please leave a comment at the end of the post or on our official account if you’d like to republish.

Editor: Wang Can

The World Economic Forum is an independent and neutral platform dedicated to bringing together diverse perspectives to discuss critical global, regional, and industry-specific issues.

Follow us on Weibo, WeChat Video Channels, Douyin, and Xiaohongshu!

"World Economic Forum"