,

:Ray Bilcliff/Pexels

Daisy Dunne

Last month, Germany became the first major economy to announce its intention to achieve "net-negative" emissions by the end of this century."Net zero" describes a state where a country’s emissions are balanced by the amount of greenhouse gases it can remove from the atmosphere, while "net negative" refers to a situation where removal exceeds emissions.Therefore, when a country achieves "net-negative" emissions, it is not only preventing further climate change caused by its own activities but also actively contributing to the global effort to curb warming.Many scenarios for achieving global climate ambitions call for us to reach net-negative emissions in the second half of this century.In these scenarios, if we fail to reduce emissions quickly enough in the short term, the world will "miss the mark" on its climate goals. And that means we’ll need to remove billions of tons of CO₂ from the atmosphere later this century to still meet those targets.Some experts are also calling on developed countries to achieve net-negative emissions by the early part of this century, arguing that they have a moral responsibility to mitigate climate change—and to create emission space for other nations as they pursue development.However, a country's ability to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere actually depends on a range of factors, including its land area, forest coverage, and population size.A researcher told Carbon Brief, the UK-based science and policy website specializing in climate change, that there’s also a risk: setting distant net-negative targets could "distract" attention from the urgent need to cut emissions within this decade.In the following article, Carbon Brief will delve into which countries have already set or are in the process of setting net-negative emissions targets, as well as the ethical and scientific arguments behind this pivotal milestone."What does 'net-negative' emissions mean?"According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, "net-negative emissions" are achieved when human-caused greenhouse gas removal exceeds human-caused greenhouse gas emissions.Professor Joeri Rogelj, a climate scientist at Imperial College London and a lead author of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change's perspective, argues that using the term "greenhouse gases" instead of the more specific "carbon dioxide" when discussing net-negative emissions "has made a significant difference."He explained that this is because, even if the world makes every effort to achieve the Paris Agreement’s goal of "limiting global average temperature rise to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels, with efforts aimed at keeping it to 1.5°C," certain non-carbon dioxide greenhouse gas emissions are nearly impossible to eliminate entirely.For example, methane emissions from rice production. Currently, there’s no technology available to eliminate these emissions entirely, and expecting rice production to cease altogether in the future is simply unrealistic.Scientists refer to these emissions as "residual non-CO2 emissions." Professor Rogelj explains:"Since there are residual non-carbon dioxide emissions, we’ll always need to achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions before we can reach net-zero carbon dioxide emissions."He added that achieving net-zero greenhouse gas emissions will require extra removal of some carbon dioxide—to offset non-CO₂ emissions that cannot be eliminated altogether."Since non-CO₂ emissions cannot be completely eliminated, we must first achieve net-zero CO₂ emissions before moving toward net-zero greenhouse gas emissions overall."That’s why proposing a national goal of achieving net-negative greenhouse gas emissions can always be interpreted as "more ambitious" than setting a net-negative carbon dioxide emissions target within the same time frame.Which countries have already achieved net-negative emissions?Although the vast majority of countries have yet to come close to net-zero emissions—let alone net-negative emissions—there are still a few Global South nations that are already removing more CO₂ from the atmosphere than they emit annually.For example, Suriname in South America, Panama in Central America, and Bhutan in South Asia.Suriname is one of the countries with the highest forest coverage in the world—over 97% of its land area is covered by trees.Trees absorb carbon dioxide as they grow, storing it in their leaves, trunks, and roots. That’s why tropical forests have particularly high carbon densities, holding about a quarter of the world’s terrestrial carbon.Suriname not only boasts dense forests but is also the least populous country in South America, with a population of just 618,000.Suriname's low carbon emissions, combined with its annual capacity to remove significant amounts of CO2 through its forests, have made the country a net-negative emitter.However, Suriname's UN climate plan—known as the "Nationally Determined Contribution"—states that developed countries "need to provide substantial international support" in order to ensure its forests continue to be protected.Colorful traditional boats on Suriname's Suriname River.

:Marcel Bakker/Alamy Stock Photo

In 2023, Reuters reported that Suriname plans to sell carbon credits—backed by forest-based emission reductions—to developed countries under the Paris Agreement.This means Suriname hopes to sell its ability to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere through forests to wealthier, more polluting developed countries. In turn, these developed nations could claim that they’ve effectively reduced their own emissions—emissions they were originally supposed to cut.Reuters reported that Suriname believes this will provide the funding needed to protect its forests.However, experts question whether developed countries should have the right to claim that their efforts to protect Suriname’s forests have helped reduce their own emissions. After all, these forests might have remained intact even without investment from developed nations. If this is indeed the case, then the real emission reductions wouldn’t have taken place in the first place.

:Peter Adams/Alamy Stock Photo

Meanwhile, Denmark announced its goals to achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2045 and reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 110% by 2050, aiming for net-negative emissions.In a document explaining the rationale behind the new goals to the Danish people, the government stated that the country "has both the opportunity and the responsibility to promote green solutions across the EU and globally."Its new goal will be "to strengthen the implementation of already-decided initiatives," which likely refers to the Paris Agreement.At the COP28 conference held in December 2023, Denmark announced the establishment of the Net-Zero Emissions Club—a coalition of countries that are either already achieving or actively working toward net-negative emissions. Members of the alliance include Denmark, Finland, and Panama, among others.Denmark's Climate Minister Dan Jorgensen addressed members of the media at the COP28 conference held in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, in 2023.Peter Dejong/Alamy Stock Photo

:Denmark's neighbor, Sweden, is the first Global North country in the world to set a net-negative target.

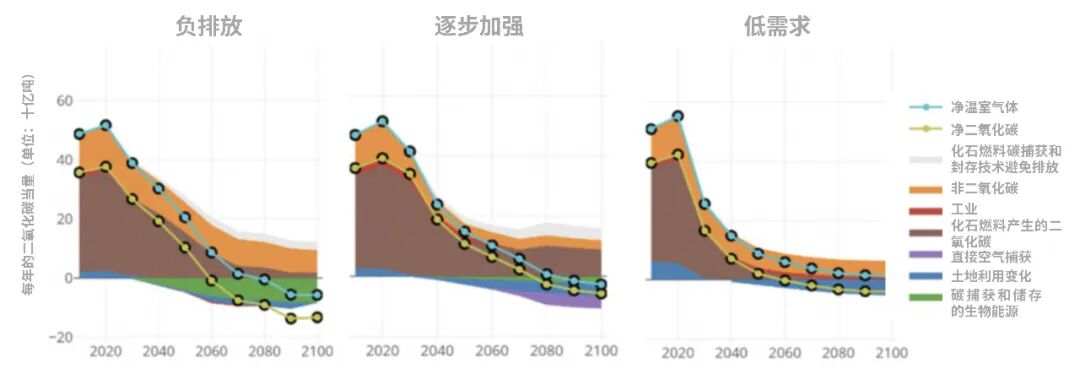

As early as 2017, it pledged to achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2045—and would soon move toward achieving net-negative emissions.In reporting on Sweden's 2017 climate law, New Scientist magazine noted that Sweden was the first country to significantly update its climate targets in line with the Paris Agreement.Scotland, meanwhile, is a Global North country that has not yet set a net-negative target but has been advised to do so.Scotland has pledged to achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2045, five years ahead of the UK's overall target of 2050.The UK's Committee on Climate Change stated that the central vision for how the UK as a whole can achieve its 2050 net-zero emissions target is that Scotland will reach "well ahead" of 2050 with net-negative emissions.In this central scenario, dubbed the "Balanced Path," Scotland is on track to achieve net-negative emissions more quickly, offsetting the slower progress in Wales, England, and Northern Ireland.The UK Climate Change Committee stated that this reflects Scotland's possession of the largest remaining ancient forests of any region in the UK, while Wales and Northern Ireland face particularly significant challenges in reducing agricultural emissions.(In the UK's most ambitious net-zero scenario, dubbed "Tailwind," the country as a whole would achieve net-negative emissions shortly after 2042. However, the UK government has yet to indicate its intention to act based on this scenario—and currently lags behind even in meeting less ambitious targets.)Another global North organization suggested to set a net-negative target is the European Union.In its recommendations released ahead of the proposed new EU 2040 targets in February, the EU’s scientific advisors stated that the bloc could enhance "the fairness of its contribution to global climate action" by adopting a net-negative target "beyond 2050."The 2021 European Climate Law pledges that the EU will achieve "negative emissions" after 2050. However, EU member states have yet to agree on specific targets for attaining net-negative emissions.Does the world need net-negative emissions to achieve its climate goals?From a scientific perspective, whether the world needs to achieve net-negative greenhouse gas emissions to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement depends on the actions countries take in the coming years.In its latest assessment of how the world is tackling climate change, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change outlined a range of scenarios detailing how global temperature goals could be achieved by the end of this century.In some of these scenarios, global emissions would decline so rapidly that achieving net-negative greenhouse gas emissions would no longer be necessary.However, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change also noted that, with global emissions remaining stubbornly high in recent years, limiting global warming to 1.5°C or 2°C is becoming increasingly challenging.By 2100, many scenarios aiming to keep temperature increases well below 2°C indeed depend on the world achieving net-negative greenhouse gas emissions in the second half of this century.Only after this, as carbon dioxide removal technologies are widely deployed worldwide and ambitious measures are taken to slash emissions—such as rapidly phasing out fossil fuels—could the situation begin to change.When greenhouse gas removal exceeds emissions (when the world becomes net-negative), global temperatures will begin to fall—and depending on the circumstances, the goal of limiting warming to below 1.5°C or 2°C could still be achievable by the end of this century.Professor Rogelj summarized the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change scenarios regarding net-negative emissions:"From a geophysical perspective, net-zero carbon dioxide emissions are an absolute necessity—we need them to halt the accelerating pace of global warming. Achieving net-zero greenhouse gas emissions, however, is more of a policy milestone. Once we reach net-zero—or even better, net-negative greenhouse gas emissions—global warming will begin to slow down gradually, dropping by just a fraction of a degree per century."While many scenarios from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change suggest that the world will achieve net-negative emissions this century, in some cases, immediate action could lead to a rapid reduction in emissions—meaning that significant carbon dioxide removal would not be necessary to keep global temperatures well below 1.5°C.The chart below is adapted from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report on how to tackle climate change, illustrating how global greenhouse gas emissions would evolve under various scenarios—ranging from keeping temperature increases to 1.5°C by 2100, to limiting them well below 2°C.The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change outlines three illustrative scenarios for limiting global warming to 1.5°C by 2100 (with negative emissions and low demand) or well below 2°C (through progressively stronger mitigation efforts).The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change outlines three illustrative scenarios for limiting global warming to 1.5°C by 2100 (with negative emissions and low demand) or well below 2°C (through progressively stronger mitigation efforts).

:2022 3.7

He added that achieving net-negative emissions as early as possible can provide developing countries with greater flexibility for economic transformation, all while prioritizing development."When we consider the global pathway that needs to be achieved, the more ambitious the countries capable of realizing this goal, the greater the room they provide for developing regions to explore alternative paths."However, it's worth noting that not all countries can achieve net-negative emissions, he added.Because a country's ability to achieve net-negative emissions is determined by a variety of factors, including land area, forest coverage, economic strength, and population size.For example, countries with relatively small populations and dense forests will be better equipped to remove more carbon dioxide from the atmosphere than they emit annually.Among the three countries that have already achieved net-negative emissions, Bhutan and Suriname are both densely forested and sparsely populated.Finland, which boasts the world's most ambitious carbon dioxide reduction targets, also has forests covering nearly three-quarters of its land area."I believe that countries with the potential to reduce carbon dioxide emissions should (set net-negative targets). However, it’s pointless to tell countries that have no capacity to remove CO2 that they must achieve net-negative emissions."Professor David Renier, a climate policy researcher at Cambridge University, has contributed to a study aimed at exploring how the responsibility for removing carbon dioxide can be fairly shared among nations.He stated that answering the question of who should be held accountable for achieving net-negative greenhouse gas emissions is actually fraught with complex challenges, as countries' technological capabilities fall far short of what’s required. He told Carbon Brief:"Determining how to assign historical responsibility for climate change is challenging. In many regions, we’ve seen people feeling angry or resistant about what their grandparents may have done—take, for instance, the issue of reparations for slavery. Distributing those responsibilities afterward has proven particularly difficult. For example, some individuals in the UK have parents who migrated from the Indian subcontinent; after all, whose emissions should they be held accountable for?"He added that focusing more on setting net-negative targets could distract countries from the urgent need to cut emissions this decade."I don’t want to see more and more countries rushing to adopt net-negative targets, simply to distract attention from the fact that they haven’t yet figured out how to achieve their net-zero goals. Or rather: ‘Well, now it’s easier for us to justify missing the 2030 target—after all, we can point to how challenging the 2070 goal will be.’"Professor Rogelj also believes that while net-negative targets could play a significant role in tackling climate change, they might distract attention unless accompanied by more immediate actions. He told Carbon Brief:"Any long-term goal without a near-term plan is untrustworthy."This article was first published in "Carbon Brief."This article is translated from the World Economic Forum's Agenda blog; the Chinese version is for reference purposes only.Feel free to share this on WeChat Moments; please leave a comment below the post if you’d like to republish.

Translated by: Wu Yimeng | Edited by: Wang Can

The World Economic Forum is an independent and neutral platform dedicated to bringing together diverse perspectives to discuss critical global, regional, and industry-specific issues.

Follow us on Weibo, WeChat Video Accounts, Douyin, and Xiaohongshu!

"World Economic Forum"